Embah: Art that seems artless

Written by Newsday on October 20, 2024

HASSAN ALI

At first glance, it can be tempting to dismiss Embah’s paintings as some primary schoolchild’s art project.

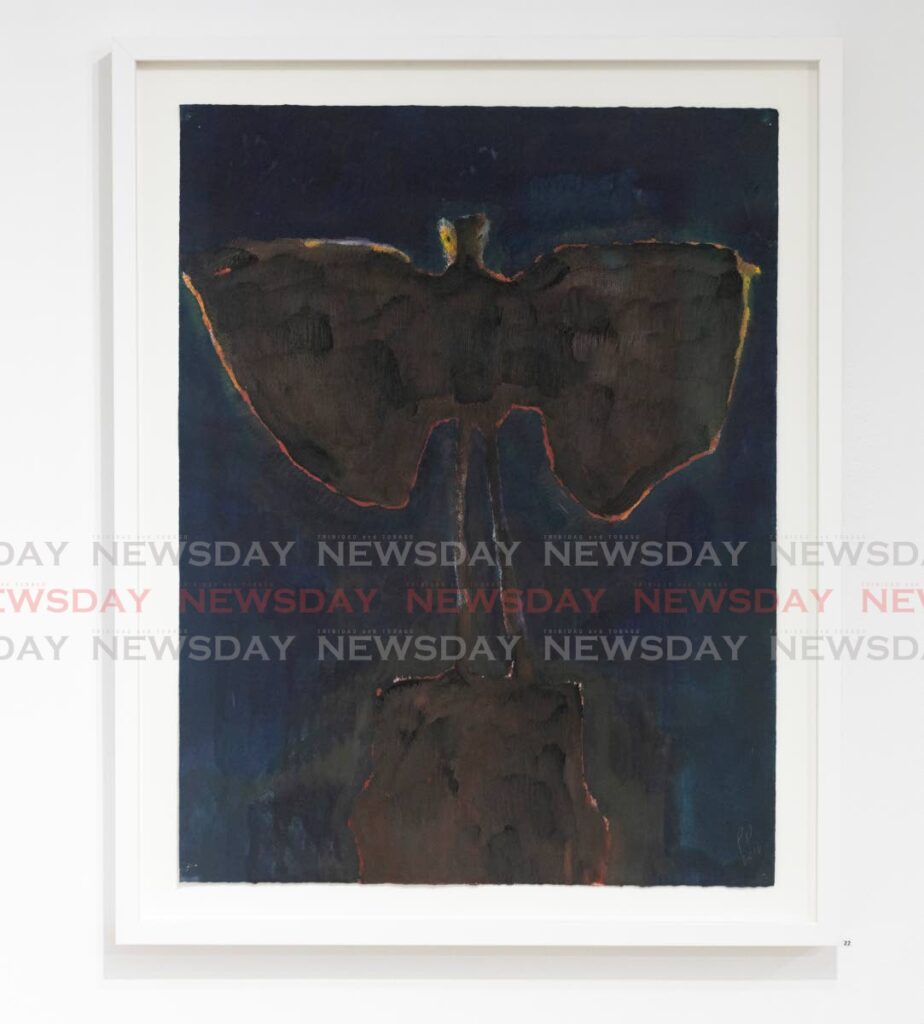

This temptation isn’t completely misguided. There is a childlikeness and a sense of play in all of Embah’s work. In Anna Walcott Hardy’s interview with Embah, featured in the catalogue for the 2015 Bat Show at the Frame Shop, the artist notes he has been labelled as “primitive” or “intuitive.”

Artist Dean Arlen has also made mention of Embah’s primitivism – specifically in a blog post memorialising the artist. Ashraph (Richard Ramsaran), curator of the Frame Shop, on the corner of Carlos and Roberts Streets, Woodbrook, says it’s Embah’s dreamy, whimsical take on his subject matter and that same childlike style which made him fall in love with the artist’s work.

Unknown (1997). – Photo by Jeff K Mayers

While other islands of the region, particularly Haiti, have greeted naivety in their visual arts with admiration, TT has generally been indifferent or turned away from this simplicity. Most often, what holds our attention in the arts is grandeur: Peter Minshall’s mas; Michel Jean Cazabon’s wide and breathy landscapes; Leroy Clarke’s raw intensity.

Embah was born Ancil Waldron in 1938. He worked as a printer at the Government Printery and as a pastry-maker before venturing into art. It’s important to note he was a multidisciplinary autodidact, because this sort of independent, curious spirit is exactly what drove his work.

He died in 2015, leaving behind many loved ones who still speak of him as a presence in their lives and in their thoughts.

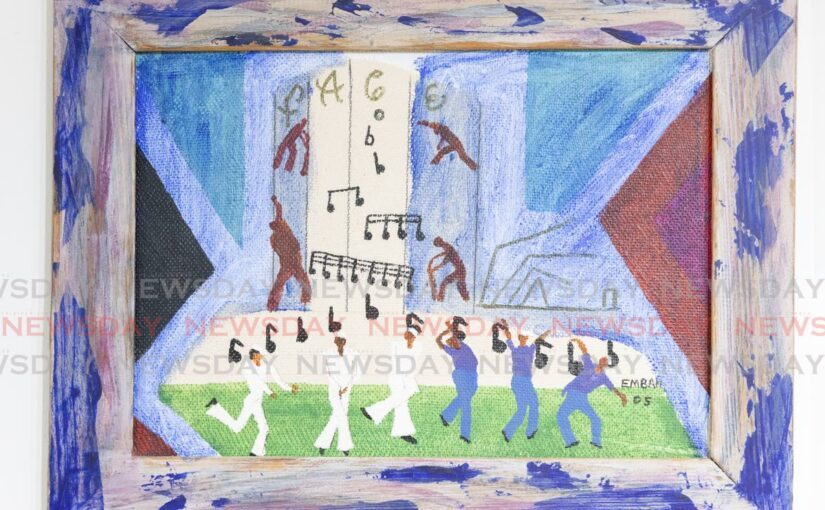

Barring Parker Nicholas’s portrait of Embah hanging from the doors of the Frame Shop, the first few paintings in the show are fantastical illustrations of this playfulness. The first piece in the show, Okay Then (2005), greets visitors with a lively scene of sailors and panmen living in the music. This is quite a common scene throughout Embah’s work and sailors are a beloved motif of his – in this show alone, eight out of 39 feature sailors. The piece immediately beneath this, Nice Music (2007), is another sailor painting.

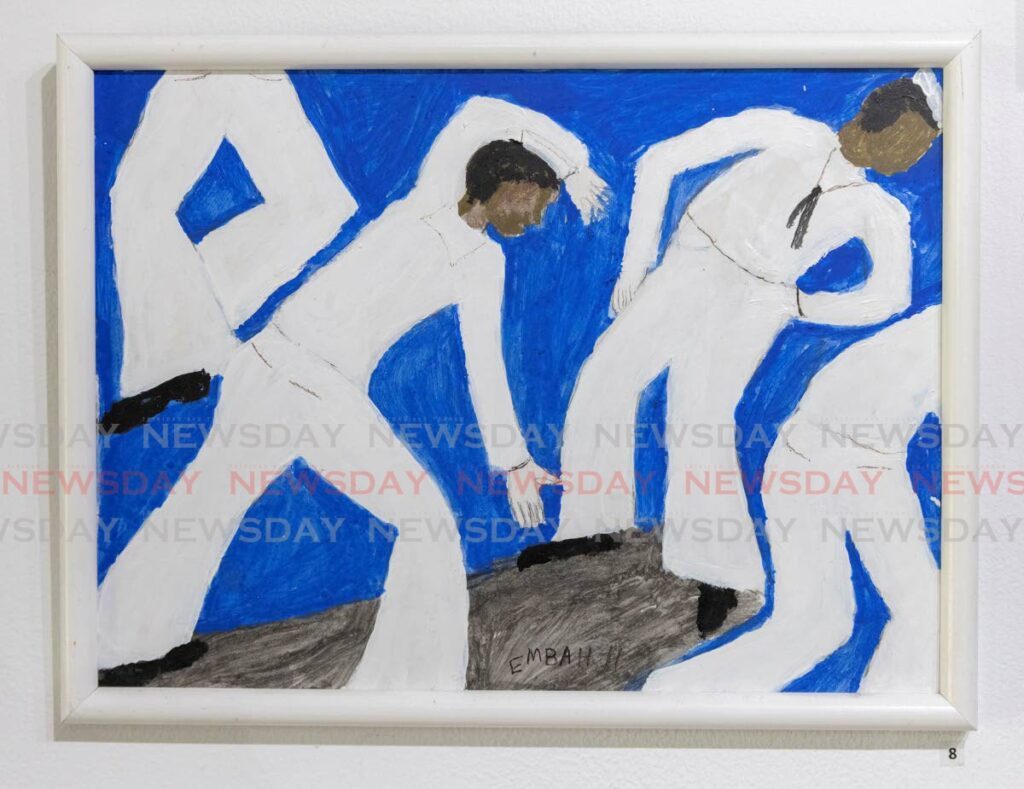

Nice Music (2011). – Photo by Jeff K Mayers

Walcott Hardy has compared Embah’s figures to Matisse’s and the similarities are visible in this piece. There’s certainly a structural resemblance in the way both Embah’s sailors and Matisse’s dancers are leaning, giving into the music, and the way both groups of dancers are suspended in this ethereal wash of colour, with only vague suggestions of solid ground. But while Matisse chose to represent primitive bodies rapt in a primitive ritual, Embah’s work remains grounded in the contemporary.

Embah was also a musician, and many of these sailor paintings are homages to Carnival and the musical culture surrounding it. In no piece is this clearer than in John’ Good or Bad (1991), in which we see a throng of sailors parading under a grand archway which features the names of all the steelbands performing at the event/competition being shown. A giant steelpan hangs from the arch. On its left, we see various shadows engaging in various sports: another homage, this time specifically to the competitive nature of even our celebrations.

Peter Doig piece titled Man Dressed as Bat (2016). – Photo by Jeff K Mayers

The last details, arguably the most striking, are the two images occupying the portion of the arch above the steelpan: the left one depicts one person whipping another; the right is a man, standing above a crowd, with a singular outstretched arm, reminiscent of depictions of Christ’s Sermon on the Mount.

These images can be thought of as occupying similar territory to the others: domination, authority, winning. They come as a reminder that this underlying, domineering drive exists in our culture and the structures which uphold our society.

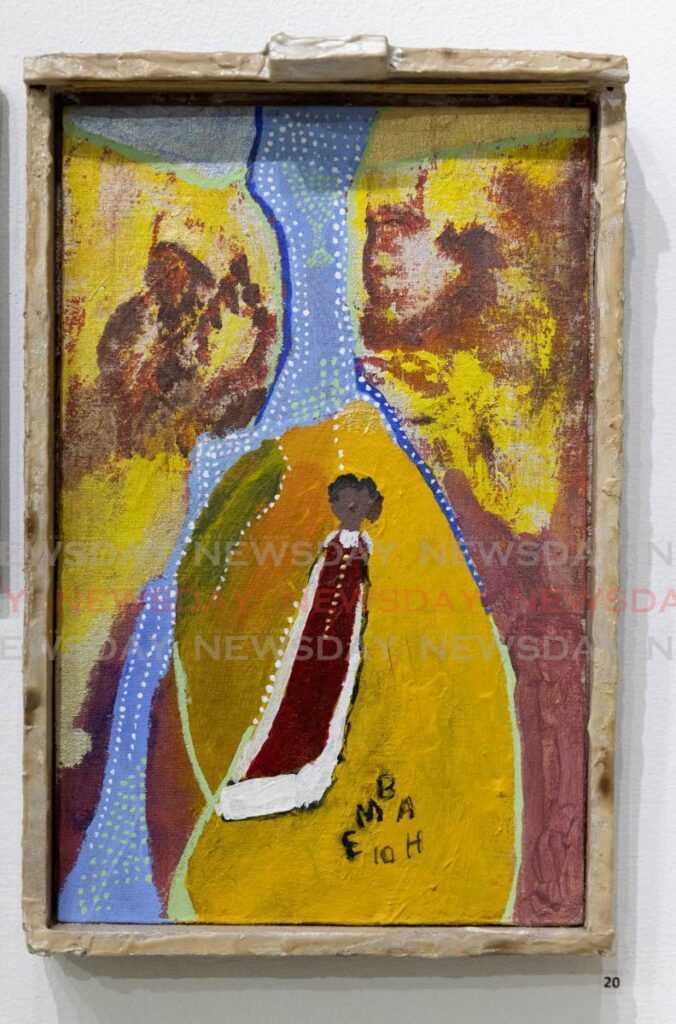

Spiritually Involves (2001). – Photo by Jeff K Mayers

This confrontation can also be seen in Unknown (2014). The painting itself is composed of two floating, closed eyelids, a blue spirit-form with a mouth in its chest, two yellow-and-white wings at either side of the spirit, and a yellow-and-white sun above the spirit, between the closed eyelids. The frame has been entirely painted over, and the sky-scene expands onto and out of the upper portion of the frame.

There is a poem written into the painting. The lines are scattered and there isn’t any assumed reading order. This is just one of many, and perhaps the most coherent arrangement of them:

“True Demockracy

Calypsonians from A to Z

From Atilla to Zandolie

Ask Popo, Slammer, Rex West.

Dem put it to de test

De letter wid de most is -S-”

John’ Good or Bad (1991). – Photo by Jeff K Mayers

The pun in “demockracy” immediately stands out. While looking at this painting in the gallery, you’ll also likely be hearing Embah’s voice in the background. His distrust of the state and other institutions was well documented on video by Banyan Archives (the video archive of the company that produced the TV programme Gayelle), among other videos of him simply working.

At the root of his distrust is a kind of childishness – specifically a refusal to be told what to do by any form of authority.

The calypsonians named here tried to test the system in their own ways: Atilla’s Treasury Scandal, Zandolie’s crass lyrics, Rex West’s parodic presentation all come to mind. It seems these wild, free souls are mocking whatever status quo, whatever democracy, would seek to confine and define their endeavours.

And why is S the letter with the most? It’s impossible to say for certain – but here’s a guess. Throughout Embah’s work, we see floating bodies, spirits dancing in the clouds and the shadows, constant religious imagery. S is most likely “spirit.”

Spirituality has clearly nurtured and guided Embah’s work. This is visible in Spiritually Involves (2001), in which we can see a figure being nurtured in a womb-like scene. In Unknown (1997) we see rolls and pages of scripture suspended throughout the image while a pot or basin bubbles over with letters and numbers. A plant grows from one of the pieces of scripture.

There is no specific name or denomination made clear in the images for Embah’s spirituality – that would likely go against his desire to freely explore his own spirit.

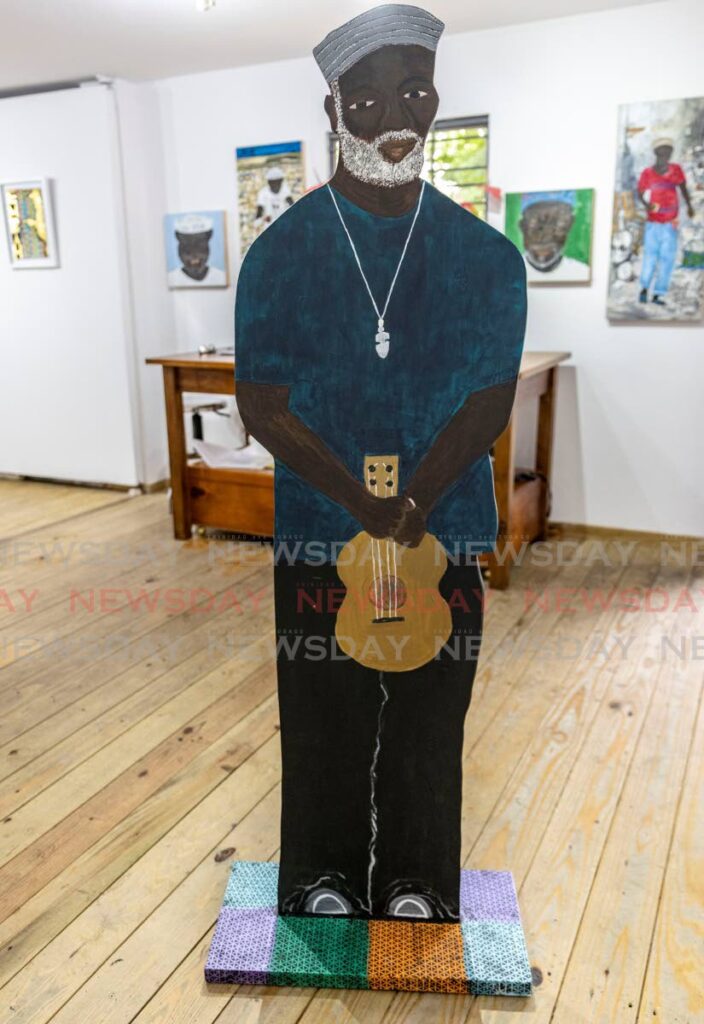

Parker Nicholas’s piece titiled Embah with de Cuatro (2024).. – Photo by Jeff K Mayers

Additionally, the exhibition includes works by students and admirers of Embah. Peter Doig’s Man Dressed as Bat (2016) is a direct reference to Embah’s own work of the same name, which was featured in the Bat show. Chris Ofili’s Embah (2017) shows Embah himself, resplendently portrayed in gold leaf, at a door with a key in his hand. Ofili’s piece is a sketch for a larger piece which was shown at the Museum of Modern Arts, New York. Paul Kain’s portraits capture Embah as he was in his daily life. Parker Nicholas’s Embah with de Cuatro (2024), a roughly life-sized statue of Embah, stands in the space gazing at his own work and the work of those he touched.

Asked why he thought it was fitting to hold an Embah show now, Ashraph said he wanted to keep Embah’s memory alive. On the one hand, it’s sentimental – this was Ashraph’s friend.

On the other hand, it’s curatorial and cultural – it’s necessary. Embah has been overlooked by TT culture. Despite being a master in his own right and finding major recognition internationally, his isn’t really a name mentioned among the titans of TT art. Perhaps it’s because he began practising art later in life – his first solo show was in 1980 – and received less public exposure than some of the aforementioned titans (most of whom were practising their art much earlier than Embah); perhaps because of his oddball, sceptical positions and personality.

In a time like ours, when most TT citizens are at one or other extreme of the paradise/banana republic spectrum of opinions, it’s refreshing to witness art that can tenderly guide one to critical thought, and which does not have to besmirch the beauty of this nation to do so.

If you can, go see EMBAH 2024 at the Frame Shop. It runs until October 26, Monday-Friday from 9am-5pm and 9am- 3pm on Saturdays. Much of his work is in private collections, so this is one of few opportunities for the public to view these pieces.

The post Embah: Art that seems artless appeared first on Trinidad and Tobago Newsday.